Caring for the Photosynthescene

Words by Mat Bate on Wurundjeri Land | Images by Charlie Perry at Sleepy Bay Tasmania, home of the Oyster Bay clan

“Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.”

I remember swimming in lakes as a child. Floating was definitely part of doing it well. Doing it well in that sense meant staying above, not going under. Then at some point you get yourself high above and jump feet first. This gets you very much under. Full submersion. A big splash. Your foot touches something down there. Mild panic. There’s that brief moment where you’re no longer going down but you’re not going up either. It’s all so curiously dark and mysteriously quiet. At that point you’re like really in it. It’s a world of the unimaginable, the unseen, and in the age of global warming (or mass extinction or whatever you want to call it) we are realising that’s where we’re at. Like, if you need proof of unimaginable magic, consider photosynthesis. Not to mention that our liveable atmosphere was created by photosynthetic microorganisms (unseeable to us) gifting the world a lot of oxygen, so take a breath and thank that magic.

Seen as such, the Anthropocene is really living inside the Photosynthescene, a word offered to us by the graphic novel for kids, Salsa Invertebraxa, by Paul Phippen AKA Mozchops: “taxpayers emit a familiar scream that rolls around the Photosynthescene”. Phippen’s choice of wording here blends things together. To “emit a familiar scream” is to do many things at once: carbon emissions, patriarchy, neo-liberalism. Then there’s the screams of extinction, unheard. And then there’s us with headphones on, running. How to listen to the many voices, human and non-human? How to develop ecological awareness in the face of it all?

Living within this ecological crisis, and waking up to it, feels like a kind of vertigo, like everything is spinning and moving and screaming and it’s hard to stay straight. It’s like a kind of bending sensation. It’s very weird, and for us humans some of it has to do with the feeling that we’re the problem and the solution and just an innocent bystander. Quite tangled isn’t it. It’s all really very strange, and it’s what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls “global weirding”. The weirdness bit though is where it gets interesting. Things get blurry and start to overlap. Boundaries fall into each other. Of course, this modern wave to ecological awareness – where we start seeing non-humans as persons and photosynthesis as something like magic – has been catalysed by global warming and it’s 100% terrifying. Unless you do heaps of yoga the bending and spinning is painful. But then again maybe we should all do more yoga and stretching. Global weirding is connected to that buzz word “paradigm shift”, and it’s got something to do with challenging a powerful modern mantra.

“Living within this ecological crisis, and waking up to it, feels like a kind of vertigo, like everything is spinning and moving and screaming and it’s hard to stay straight.”

Out of sight, out of mind. As in, presuming what is not in sight is outside of our responsibility. The unseen is cast out, wonder is reduced, magic is squashed; photosynthesis is an equation, Earth is a mine, nature’s over there, oceans are blue and cold, how are you I’m good. This is one way to look at the climate crisis: a mistreatment of what we‘re not seeing (and hearing, asking, etc.). Think about the state of our great underworlds: the soil and the ocean. Two primary links in the carbon cycle. Globally, it’s estimated that we’re losing about 12m hectares of topsoil every year and about 10% of the plastic produced every year ends up in the ocean, choking marine life. So much carbon has gone into our oceans recently (our oceans absorb 25% of the carbon we emit) that ocean acidity (more carbon in the water = greater acidity) hasn’t moved this quickly since the last mass extinction event, 56 million years ago.

Underground and underwater; two places we cannot readily see, two places we so easily destroy. Out of sight, out of mind. The twisted thing here is that our vandalism now provides a good example of what not to do, which prompts observing/listening/imagining, which prompts ecological awareness. It’s like when someone does graffiti on a wall near your house. When that happens, you realise you’ve never actually seen that wall. But now you see the wall.

I’m aware I’ve taken a bit of a winding course to get here, but ultimately, I’m talking about our current regenerative journey (AKA ecological awareness). Regeneration is a process of widening our field of vision, so we become more fully responsible for things seen and things unseen. It’s a process of wonder, reciprocity, gratitude towards the bizarre, the unimaginable. It’s a process of re-animating the world, because everything is saying hello. David Abram, the cultural ecologist and ex-magician, explains this well. He defines climate change as “the simple consequence of forgetting the holiness of this mysterium in which we’re bodily immersed.” For Abram, the climate crisis emerged from the act of losing/not seeing/forgetting how miraculous and bizarre the whole thing is. It’s an emergent property of a mechanistic culture, one that sees everything as rather inanimate, rather dead. In this sense, our image of the world needs resuscitating. I’m definitely not in a position to tell anyone how that happens, I’m as confused as the next person, but I think it has something to do with sharing stories.

“Regeneration is a process of widening our field of vision, so we become more fully responsible for things seen and things unseen. It’s a process of wonder, reciprocity, gratitude towards the bizarre, the unimaginable. It’s a process of re-animating the world, because everything is saying hello.”

We have always animated the world with stories. Stories are so central to the way we roll that if I just leave that sentence there it stands up. And of course, in many environmental organisations, their theory of change usually has something that says: “change the narrative”. And it’s true right, we are our stories. But it’s not enough to change a narrative and we’re all good. Stories are shared things, so we also need a slogan that says: “share the story”. Or maybe just “share”. This is why I think children’s books are so interesting now, because they’re really designed knowing that it’s more than likely two people, at least, will be reading together. And given we’re all children when it comes to climate change, like really what is actually going on, maybe we all need to read children’s books, get back on the same page so to speak. Instead of calling them books for kids maybe we need to call them books for little-big people, invite everybody to the reading. Let’s get everyone really in it and talk about unseen landscapes, unheard songs and the mysterium of our Photosynthescene.

It’s like what Mary Oliver said: “Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.” I guess that’s what I’m really trying to say. Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable. Share it around.

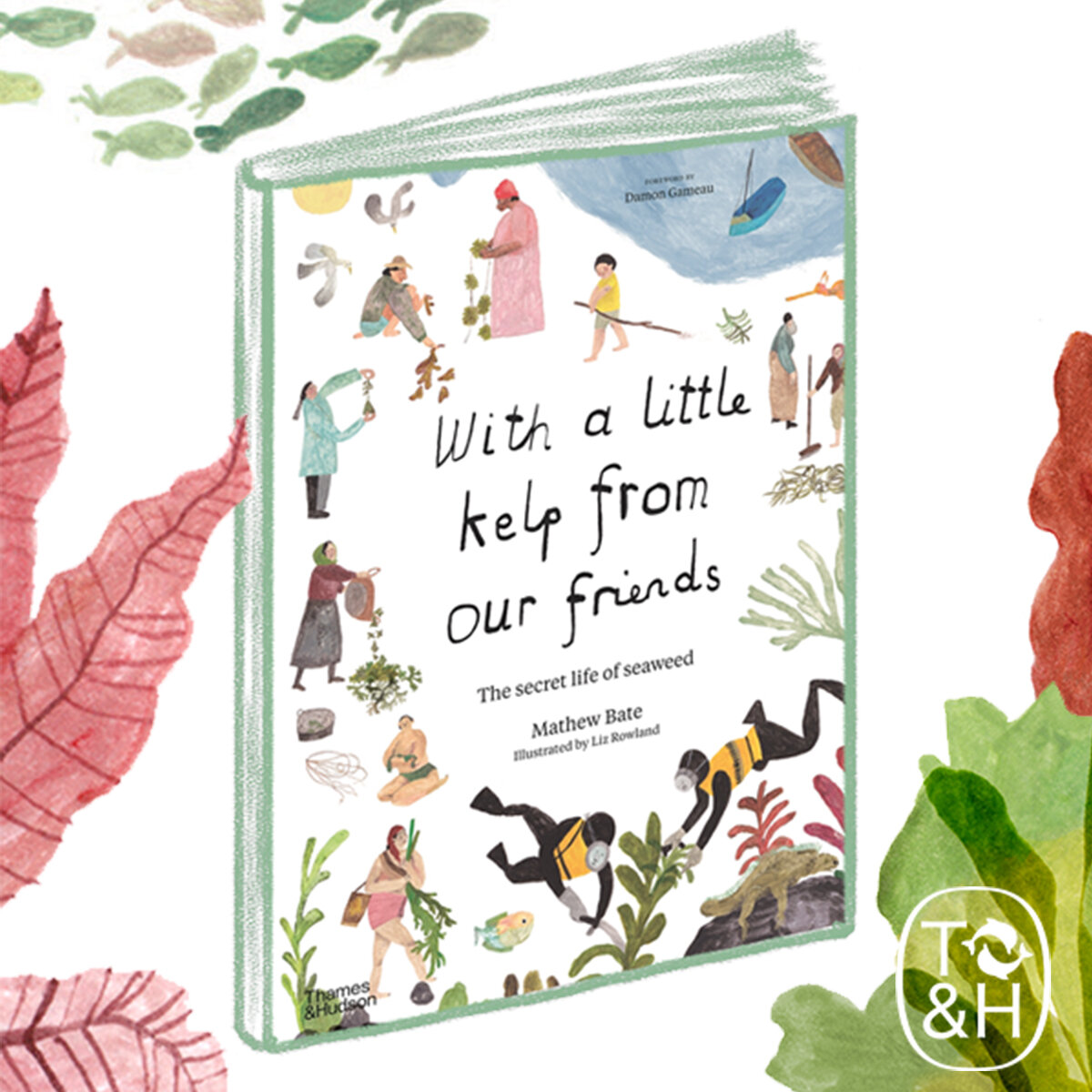

With a Little Kelp From Our Friends

Mat's book for little-big people, With A Little Kelp From Our Friends: The secret life of seaweed, is out now with Thames and Hudson. Find it online or at your local bookstore.